Dima’s body of practice traces her notion of place through extractions and case studies. She approaches place from the perspective of language. First, literary. Struggling with defining place, she defers it, attempting to understand displacement, replacement, emplacement, and misplacement first. When in distance from place, she looks for vivid image. When encountering ocularcentrism, she circles back to song, voice, and speech; language. “Orality in Arabic poetry, especially pre-Islamic, was rooted in the oral, developed within an audio-vocal culture. It indicates that poetry did not come down to us in written or visual form, but was anthologized in memory and preserved through oral transmission.” (Adonis, 1985) So then, phonetic. She conducts a single case study of the lullaby: نامي نامي يا زغيري , nami nami ya zġireh (sleep little one), composed by Marcel Khalife and vocalised by Oumeima Khalil in 1980 in Beirut. She transcribes the lullaby, phonetically, then derives its metre, rhythm, and melody by memory.

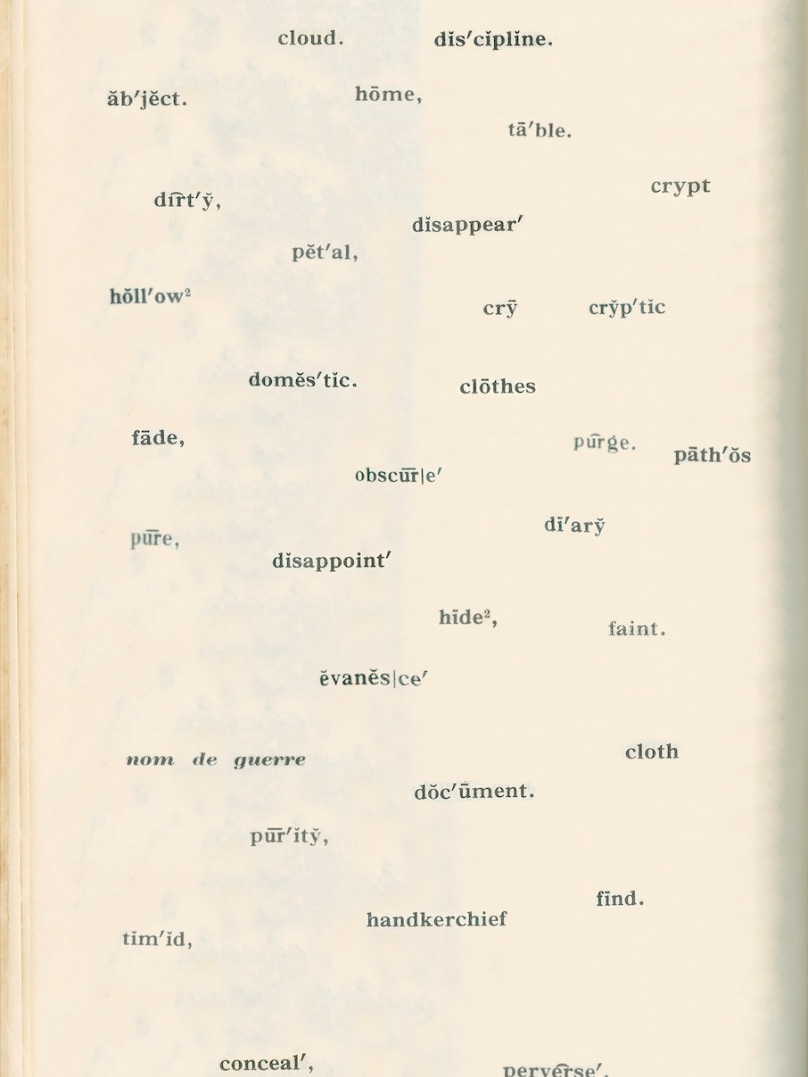

In Arabic, place is not a word at all. Even when studied as a noun, place is a concept alluded to based on an action in relation to its spatial-temporal locus.

prefix + tuned verb

The noun for place is just a transformed word that begins with the prefix (ma مَـ ) and a verb tuned to a constant grammatical weight: مَـ ـفْعَلٌ or مَـ ـفْعِلٌ . So, yes, place can be directly translated to مكان, but only because that is the most general way to describe a place; as where something (anything) has been or has happened. For place according to the dictionary, is also مَنْزِل، مَلْعَب، مَرْسَم and so on. It is just مَـ ـفْعَلٌ .